CODING:

As if you didn’t already have enough on your plate, CMS has recently rolled out more than 250 new diagnosis codes! On Oct. 1, 2024, CMS updated the code set, and of course, they changed codes for obesity. Although updates to the terminology were woefully overdue (getting rid of the words “morbid obesity due to excess calories” brings us out of the dark ages), these changes will alter your code selections during E&M visits – and potentially your ability to get reimbursed for visits when treating obesity.

When treating obesity, it’s recommended that clinicians use the appropriate E code followed by the appropriate Z code – to increase diagnostic accuracy and available treatment options.

E Codes: Adults:

E66.811 (Obesity, class 1: BMI 30-34.9)

E66.812 (Obesity, class 2: BMI 35-39.9)

E66.813 (Obesity, class 3: BMI ≥ 40)

* the code E66.3 (Overweight: BMI 25-29.9) has not been updated

Z Codes: Adults:

Z68.25 – BMI 25.0-25.9

Z68.26 – BMI 26.0-26.9

Z68.27 – BMI 27.0-27.9

Z68.28 – BMI 28.0-28.9

Z68.29 – BMI 29.0-29.9

Z68.30 – BMI 30.0-30.9

Z68.31 – BMI 31.0-31.9

Z68.32 – BMI 32.0-32.9

Z68.33 – BMI 33.0-33.9

Z68.34 – BMI 34.0-34.9

Z68.35 – BMI 35.0-35.9

Z68.36 – BMI 36.0-36.9

Z68.37 – BMI 37.0-37.9

Z68.38 – BMI 38.0-38.9

Z68.39 – BMI 39.0-39.9

Z68.41 – BMI 40.0-44.9

Z68.42 – BMI 45.0-49.9

Z68.43 – BMI 50.0-59.9

Z68.44 – BMI 60.0-69.9

Z68.45 – BMI ≥ 70

Z Codes: Children (ages 2-19 in the coding universe):

Z68.54 (BMI 95th percentile to less than 120% of the 95th percentile: Obesity Class 1)

Z68.55 (BMI 120% to less than 140% of the 95th percentile: Obesity Class 2)

Z68.56 (BMI pediatric 140% of the 95th percentile and above: Obesity Class 3)

Note: although the following codes exist, they have been deemed non-billable codes. (I know, what’s the point in having them, right?)

Z68 – BMI

Z68.3 – BMI 30-39

Z68.4 – BMI 40 or greater

Eating Disorders (commonly coexisting in patients with excess weight):

The following have become parent codes:

F50.2 (Bulimia nervosa)

F50.81 (Binge eating disorder)

Beneath each of the parent codes, there will now be a 5th character option. These descriptions are general – clinician discretion determines whether a case is mild, moderate, severe, or extreme:

5th character 0: Mild. This disorder grade involves occasional calorie restriction, binging, or purging, depending on the disorder. Patients with a mild grade will have symptoms, but they’re not likely to affect daily functioning.

5th character 1: Moderate. This disorder grade involves more regular calorie restriction, binging, or purging. This is where the disordered eating begins to interfere with the patient’s daily life; they might report that the disorder has impacted social activities, work, or school. The change in the patient’s weight or health might be evident, but it is not yet life-threatening.

5th character 2: Severe. This disorder grade involves persistent — sometimes compulsive — behaviors that the patient has difficulty controlling. The disordered eating for severe patients will significantly impair their daily life, along with their physical and emotional health. Patients with severe eating disorders might be suffering from severe weight changes, nutritional deficiencies, and psychological distress.

5th character 3: Extreme. This disorder grade is the highest, marked by extreme, intense, and frequent disordered eating. Patients with extremely disordered eating will have life-threatening symptoms, such as dangerously low weight, organ failure, or other severe complications. A person with extreme disordered eating might even be refusing to eat almost entirely.

5th character 4: Use this character when the eating disorder is in remission.

5th character 9: Use this character when the eating disorder is unspecified.

Thoughts and Musings Regarding the Risks Associated With Coding for Obesity:

Due to a dramatic uptick in the number of patients seeking treatment for excess weight from healthcare providers, the insurance industry has adapted. Although there are rare instances where these adaptations are truly helping patients, more often than not, they are less than helpful.

All health plans have exclusions; things they don’t cover. Although self-funded employers sometimes remove these exclusions, it’s not standard procedure. Braces and infertility treatments are traditionally excluded, as are “weight loss services.”

When I first began treating obesity under the umbrella of health insurance, because I was providing comprehensive obesity treatment; screening for and managing comorbidities, I rarely saw medical office visits being denied for being a “non-covered service.” After all, what my team and I do at Heartland Weight Loss goes far beyond simply helping patients lose weight.

In 2023, this changed. Our biggest carrier suddenly started denying the vast majority of the visits we submitted. They retracted hundreds of previously paid visits. Despite writing hundreds of appeals, citing specific instances in which we were actively treating weight-related comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes or hypertension, the carrier refused to budge. The exclusion provided them a way to offset the increased costs caused by the uptick in obesity treatment across the entire region. We were told that all visits in which weight management was addressed would be denied – regardless of the codes we used – even if we were actively diagnosing or treating other comorbidities during the visit.

As I’m sure you can imagine, the fallout from this abrupt policy change wreaked havoc – for patients and for us internally. Unwilling to exclude all mention of weight from our chart documentation, we severed our contract with this carrier and created a self-pay option for patients unfortunate enough to be covered by them.

Since then, we have discovered that every other carrier has similar language in their base plan – allowing them to deny medical office visits if weight management is addressed. We are seeing more and more of these visits excluded each month. Because of this, we have made the difficult decision to sever our contracts with all insurance plans at the end of 2024 and move to a fully self-pay model.

This has happened in multiple locations across the country and has thus far only been implemented in small private practices. If you work for a large health system (whose strength limits large insurance carriers’ power to deny claims), you may be protected from this devastating practice. However, as we enter a new benefit year, following one of the biggest increases in premiums in decades, we are likely to see more and more denials across the board and it’s best to be prepared.

If a carrier decides to deny any visit during which obesity is managed, even indirectly, the following tips and tricks may not be of any help to you, but if they approach it with a softer stance, these could potentially save you a lot of hassle – and revenue.

The Obesity Medicine Association defines obesity as:

“a chronic, progressive, relapsing, and treatable multi-factorial, neurobehavioral disease, wherein an increase in body fat promotes adipose tissue dysfunction and abnormal fat mass physical forces, resulting in adverse metabolic, biomechanical, and psychosocial health consequences.”

There are numerous benefits to treating obesity as a disease:

- Treating obesity may reduce premature mortality.

- Treating obesity results in improved cardiovascular effects, such as improved atherosclerosis, thrombosis, hypertension, and heart failure.

- Treating obesity results in improved metabolic effects, such as improved insulin resistance, hepatosteatosis, and gout.

- Treating obesity results in improved mechanical effects, such as improved obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, and intertriginous skin disorders.

- Treating obesity may reduce the onset of certain cancers, improve response to cancer treatments, and reduce the recurrence of cancers.

- Treating obesity results in improved psychological effects, such as improved fatigue, anxiety, depression, and body image.

- Treating obesity may improve quality of life by improving dyspnea, and mobility, and decreasing polypharmacy.

- Treating obesity improves individual and societal recognition of weight bias.

- Treating obesity may improve certain causes of infertility and hypogonadism.

- Treating obesity can help mitigate epigenetically transmitted increased risk of obesity and metabolic disease in future generations

Sadly, most healthcare providers treat obesity-related comorbidities first, and, as part of the treatment of these coexisting conditions, mention to patients that they should also lose some weight as part of the treatment. When put that way, it sounds pretty bad, right? This is the way we were taught to practice medicine, though – so if it sounds familiar, don’t judge yourself too harshly!

“Treat obesity first” is an alternative concept that has a lot of merit. Focusing on obesity as the foundational problem, rather than dancing around the topic, putting out all of the other fires first, actually makes a lot of sense. This doesn’t mean ignoring acute emergencies or withholding treatment altogether for chronic diseases, but it means considering the individual as a whole person – not a sum of his or her diagnoses.

(If, someday, you ever want to dive deeper into this concept, I would love to go there with you. It’s a subject I’m incredibly passionate about and one that doesn’t get much notice – understandably, as it’s decently complex. Although we like to blame obesity as the biggest culprit driving chronic diseases and decreasing our life expectancy, it’s not the biggest problem. Surely you have patients who have chronic lifestyle diseases (type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, MASLD, OSA, etc) who don’t have obesity, right? Or who had these diseases before developing obesity? If obesity is the driver for these diseases, how can they exist in the absence of obesity? Because all of these diseases, including obesity, are manifestations of something bigger happening inside the body – something called metabolic dysfunction – driven by insulin resistance and impaired mitochondrial function. This problem most often manifests itself by disrupting energy storage in the body, thus resulting in obesity, but it can manifest in other organ systems as well – alongside, or completely independent of, excess energy storage.

The good news is that treating obesity usually causes improvement in these other manifestations.

The bad news is that unless you attack the core problem – the metabolic dysfunction – as soon as you stop treating obesity, the weight comes back on – and the other comorbidities come barreling back as well.

Again, for most patients, treating obesity is still a huge improvement over NOT treating it, so go for it, but it helps to understand why treatment focused on obesity alone is considered to be necessary lifelong and why weight regain is almost guaranteed when someone stops taking an anti-obesity medication and they haven’t done the deeper work of solving the metabolic dysfunction problem. For patients willing to take the plunge, this is what we work so hard on at Heartland Weight Loss – we internally refer to it as practicing mitochondrial medicine or metabolic medicine – it’s what we love to do!)

Back to the primary topic:

I’m not going to wax long about the rules of coding and billing – although I’ve had to do both for many, many years and I know more than I ever wanted to know about them, you just need the basics – especially if you have people working for you that do them for you (which, if you’ve never thought about it, is a huge luxury)!

The diagnosis codes you attach to a chart note should match the subject matter of the note – in order of relevance. In other words, if the primary reason the patient is being seen is to treat her obesity, obesity should be the first diagnosis code attached to the visit.

If, however, the patient is being seen to manage hypertension and part of the treatment for her hypertension is to lose some of her excess weight, you can code hypertension first, followed by obesity.

I can’t tell you how to code visits (that would be illegal!) but I will tell you that AI systems that scrub claims are often programmed to deny claims when obesity is listed as the primary diagnosis code. If, however, obesity is the second or third diagnosis code listed, the claims often pass through unnoticed.

In the olden days of Obesity Medicine, it was common practice to attach obesity-related comorbidities to chart notes first, followed by the diagnosis of obesity (or overweight or severe obesity – whichever is most appropriate – we will get to that later as that has undergone significant revisions recently and goes into effect in 2025).

Although it was the standard practice amongst pretty much all Obesity Medicine clinicians for many years (and is still widely practiced today), when our biggest carrier was in the process of upholding their “obesity exclusion”, their coding specialist informed me that the process would no longer be tolerated. She and her team were on a mission to ensure that if the patient visited specifically to talk about or treat her excess weight, regardless of the comorbidities addressed as part of that treatment, the billing provider used the obesity code as the primary diagnosis.

She informed me that if the coding team gets suspicious that a clinician is treating obesity as a primary diagnosis (and not coding visits appropriately to reflect that practice), she and her team will start an investigation. This means they will manually comb through charts to determine if the coding matches the chart note and the treatment prescribed and will deny the claim if the treatment/coding doesn’t match up. And, if obesity treatment was the primary focus of the visit and obesity treatment is an excluded service, the visit will be denied. This will trigger a retrospective chart review of the patient’s other claims, which will also be subject to denials if it appears the visit was focused on treating obesity.

Again, the way the obesity exclusion is worded, the carriers could theoretically deny reimbursement for any visit during which obesity is even mentioned – even if the visit is centered around treating endometrial hyperplasia or diabetic retinopathy and managing obesity as part of that treatment is noted only briefly, but it’s unlikely they would do this at scale – especially if you work for a large health system that funnels a great deal of volume their way. If you work for a small practice that doesn’t have the power of a large health system behind you, tread very carefully in these waters. Learn from my experience! Carriers are NOT nice to small practices! Either way, you should be aware of it.

No matter what, I would encourage you to structure your chart notes to reflect what you do and to support your coding. If you are treating obesity as the chief complaint and treating obesity doesn’t affect other comorbidities, it may be the only code you can attach to the visit.

If, by treating obesity, you can reduce someone’s dose of an antihypertensive medication, coding for obesity and hypertension is warranted. The order in which you arrange those diagnosis codes is up to you (and potentially your coding/billing team).

Other Things That I’ve Learned The Hard Way:

There are a lot of Z codes that are relevant when treating patients for excess weight. Although using them won’t usually get your visit flagged and audited, don’t use them as the first code! AI systems don’t like Z-codes when they are the primary code and often reject the claim outright, without considering any of the codes that follow. However, when you don’t have other codes to attach to the visit, they can support the treatment of obesity:

Z71.3: dietary counseling and surveillance

Z71.82: exercise counseling

Z72.3: lack of physical exercise

Z72.4: inappropriate eating habits

Z72.821: inadequate sleep hygiene

Z86.32: history of gestational diabetes

Z98.84: history of bariatric surgery

Z82.4: family history of heart disease

Z83.3: family history of type 2 diabetes

We will move on to billing here in a second. As you will learn shortly, managing patients with obesity is typically a complicated process, involving quite a bit of risk. As long as the chart note supports it, this usually allows clinicians to bill for a moderate complexity visit (99204 or 99214). However, for reasons I can’t fully explain (that are likely illogical in the first place), using the following code along with a 99214 code often results in a denial. It’s often just fine when used in a low-complexity visit (99213), but beware if you are using it to support anything beyond that:

Z79.899: other long-term (current) drug therapy

These are both valid clinical diagnoses and support the need for obesity treatment, but beware when trying to use them alongside E+Z codes. The computers often don’t like seeing them used alongside codes for obesity and/or BMI. They often get fussy if they are used regularly as well.

R63.5: abnormal weight gain

R63.2: polyphagia

BILLING:

I don’t have a certification in medical billing, so take all of this with a grain of salt. Everything that follows is based on my research, learned out of sheer necessity, and constitutes helpful advice – not professional recommendations. Always rely on trained professionals when it comes to submitting claims to insurance companies! The information that follows comes from the training materials I put together to train my staff when we were submitting visits to insurance.

The information was pulled from the following two documents:

2023 CPT E/M descriptors and guidelines (ama-assn.org)

Coding Level 4 Office Visits Using the New E/M Guidelines | AAFP

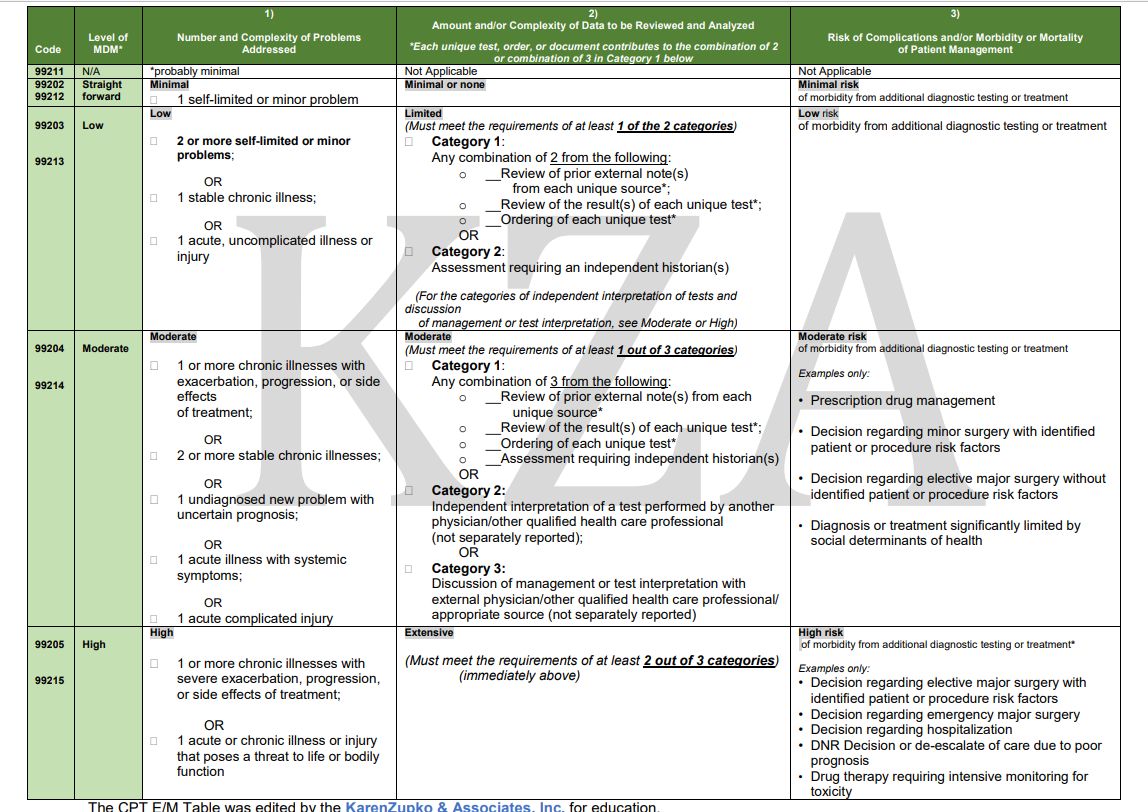

According to the 2023 CPT® E/M Guideline Revisions, four types of medical decision-making (MDM) are recognized: straightforward, low, moderate, and high.

Medical Decision Making (MDM) is defined by three elements. To qualify for a particular level of MDM, TWO OF THE THREE ELEMENTS FOR THAT LEVEL OF MDM MUST BE MET. The elements are:

1. The number and complexity of problem(s) that are addressed during the encounter:

Comorbidities and underlying diseases, in and of themselves, are not considered in selecting a level of E/M services unless they are addressed, and their presence increases the amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed or the risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.

The term “risk” as used in these definitions relates to risk from the condition. While condition risk and management risk may often correlate, the risk from the condition is distinct from the risk of the management.

A problem is a disease, condition, illness, injury, symptom, sign, finding, complaint, or other matter addressed at the encounter, with or without a diagnosis being established at the time of the encounter. A problem is addressed or managed when it is evaluated or treated at the encounter by the physician or other qualified healthcare professional reporting the service. This includes consideration of further testing or treatment.

A stable, chronic illness is a problem with an expected duration of at least one year or until the death of the patient. For the purpose of defining chronicity, conditions are treated as chronic whether or not stage or severity changes (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes and controlled diabetes are a single chronic condition). “Stable” for the purposes of categorizing MDM is defined by the specific treatment goals for an individual patient. A patient who is not at his or her treatment goal is not stable, even if the condition has not changed and there is no short-term threat to life or function. For example, a patient with persistently poorly controlled blood pressure for whom better control is a goal is not stable, even if the pressures are not changing and the patient is asymptomatic. The risk of morbidity without treatment is significant.

An acute, uncomplicated illness is a recent or new short-term problem with a low risk of morbidity for which treatment is considered. There is little to no risk of mortality with treatment, and full recovery without functional impairment is expected. A problem that is normally self-limited or minor but is not resolving, consistent with a definite and prescribed course is an acute, uncomplicated illness.

A chronic illness with exacerbation, progression, or side effects of treatment is a chronic illness that is acutely worsening, poorly controlled, or progressing with an intent to control progression and requiring additional supportive care or requiring attention to treatment for side effects.

A stable, acute illness is a problem that is new or recent for which treatment has been initiated. The patient is improved and, while resolution may not be complete, is stable with respect to this condition.

2. The amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed.

Analysis is the process of using the data as part of the MDM. The data element itself is included in the thought processes for diagnosis, evaluation, or treatment. Data are divided into three categories. Each unique test, order, or document is counted.

Tests: Tests are imaging, laboratory, psychometric, or physiologic data.

A clinical laboratory panel (e.g., BMP) is a single test

The 2020 CPT book, when talking about what constitutes data, defines physiologic data as (e.g., weight, blood pressure, pulse oximetry, respiratory flow rate)

Documents: These data include medical records and/or other information that must be obtained, ordered, reviewed, and analyzed for the encounter.

Orders: if we count ordering a test as one data point in one encounter, we can’t count it again for interpretation. However, ordering a test may include those considered but not selected after shared decision-making. For example, a patient may request diagnostic imaging that is not necessary for their condition and a discussion of the lack of benefit may be required. These considerations must be documented.

3. The risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.

One element used in selecting the level of service is the risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management at an encounter. This is distinct from the risk of the condition itself.

Risk: The probability and/or consequences of an event. The assessment of the level of risk is affected by the nature of the event under consideration. For example, a low probability of death may be high risk, whereas a high chance of a minor, self-limited adverse effect of treatment may be low risk.

Definitions of risk are based on the usual behavior and thought processes of a physician or other qualified healthcare professional in the same specialty. Trained clinicians apply common language usage meanings to terms such as high, medium, low, or minimal risk and do not require quantification for these definitions (though quantification may be provided when evidence-based medicine has established probabilities).

For the purpose of MDM, the level of risk is based upon the consequences of the problem(s) addressed at the encounter when appropriately treated. Risk also includes MDM related to the need to initiate or forego further testing, treatment, and/or hospitalization.

Morbidity: A state of illness or functional impairment that is expected to be of substantial duration during which function is limited, quality of life is impaired, or there is organ damage that may not be transient despite treatment.

Social determinants of health: Economic and social conditions that influence the health of people and communities.

** If you want to bill on time (really only useful if you don’t have to do anything at all with your brain during the visit)

99204 = 45-59 minutes

99213 = 20-29 minutes

99214 = 30-39 minutes

Time = the total time on the date of the encounter. It includes both the face-to-face time with the patient and/or family/caregiver and non-face-to-face time personally spent by the physician and/or other qualified health care professional(s) on the day of the encounter (includes time in activities that require the physician or other qualified health care professional and does not include time in activities normally performed by clinical staff).

The physician or other qualified health care professional time includes the following activities when performed:

- preparing to see the patient (e.g., review of tests)

- obtaining and/or reviewing separately obtained history

- performing a medically appropriate examination and/or evaluation

- counseling and educating the patient/family/caregiver

- ordering medications, tests, or procedures

- referring and communicating with other health care professionals (when not separately reported)

- documenting clinical information in the electronic or other health record

- independently interpreting results (not separately reported) and communicating results to the patient/family/caregiver

- care coordination (not separately reported)

From the AAFP document (written for those of us in medicine who don’t have a certification in coding and don’t speak that language well):

To make it easier to understand: substitute “level 4” for the term “moderate” as we take a look at what qualifies in each category (problems, data, and risk).

Level 4 PROBLEMS include the following:

- One unstable chronic illness (for coding purposes “unstable” means not at goal: for example, hypertension in patients whose blood pressure is not at goal or diabetes in patients whose A1C is not at goal),

- Two stable chronic illnesses (e.g., controlled hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or heart disease),

- One acute illness with systemic symptoms (e.g., pyelonephritis or pneumonia),

- One acute complicated injury (e.g., concussion),

- One new problem with uncertain prognosis (e.g., breast lump).

Level 4 DATA includes the following:

- One x-ray or electrocardiogram (ECG) interpreted by you,

- Discussion of the patient’s management or test results with an external physician (one from a different medical group or different specialty/subspecialty),

- A total of three points, earned as follows:

- a) One point for each unique test ordered or reviewed (panels count as one point each; you cannot count labs you order and perform in-office yourself),

- b) One point for reviewing note(s) from each external source, and

- c) One point for using an independent historian.

Level 4 RISK includes the following:

- Prescription drug management, which includes ordering, changing, stopping, refilling, or deciding to continue a prescription medication (as long as the physician documents an evaluation of the condition for which the medication is being managed),

- The presence of social determinants of health that significantly limit a patient’s diagnosis or treatment,

- A decision about major elective surgery or minor surgery

What about Medicare?

Because contracting with Medicare involves a lot of regulations and compliance (and failing to do it perfectly can come with some pretty hefty fines and punishments) and I have never had the overhead to employ staff to oversee this, since being in private practice, I have opted out of Medicare.

Coding within the Medicare system is different than commercial insurance and I can’t help you much with that. From what I’ve gathered during billing/coding CME programs that I have attended, when done correctly, there is potential for higher reimbursement from Medicare when managing obesity.

For example:

G0447 can be used for reimbursement for preventive health counseling. There are specifications in terms of what can be discussed and the time spent, but it may be worth looking into

There are also a lot of options for reimbursement for remote patient monitoring (RPM). We tried this over the years with commercially insured patients and it always proved to be a disaster (costs typically went to their deductibles, which made most of them angry), so we haven’t done it in years, but it may be worth a shot – to help offset the decrease in reimbursement you will likely see as a result of treating obesity.

99453, 99454, 99457, and 99458 are RPM codes

Finally, Medicare also has options for reimbursement for chronic care management (CCM). Time spent doing prior authorizations (a subject of another email) counts toward this time, as does time spent talking with patients on the phone. Reimbursement for CCM may be another way to augment the decreased income you will likely see if/when you choose to treat more and more patients for obesity.

99490, 99491,99487, and 99489 are CCM codes

That’s probably more than you ever wanted to know about coding and billing – but I hope at least some of it was helpful!

What follows are some tables I grabbed from relevant publications that helped me understand how the system works